Editor's note: Exactly 130 years ago today, on September 25, 1890, President Wilford Woodruff wrote in his journal that “After Praying to the Lord & feeling inspired by his spirit I have issued . . . [a] Proclamation.” That proclamation is now known as the Manifesto and was published in the Doctrine and Covenants as Official Declaration 1. This article originally ran on LDS Living in 2017 and is being shared again for the 130th anniversary of the day Official Declaration 1 was released to the public on September 25.

Throughout the history of the Church, the practice of plural marriage has been viewed at different times with defensiveness, derision, or outright bewilderment. However, recent works produced by scholars working on the Joseph Smith Papers Project, and independent researchers such as Brian and Laura Hales, Kathryn Daynes, and others have helped bring to light some vital facts that help us better understand the nature of this practice. Here are five things you might not have known about plural marriage:

1. Plural marriage was revealed early in the history of the Church.

The 2013 edition of the Doctrine and Covenants notes that some of the principles concerning celestial marriage and plural marriage may have been known “as early as 1831” (Doctrine & Covenants 132 introduction). There is evidence that suggests that Joseph Smith began to ponder the principles surrounding the practice as part of the work that became known as the Joseph Smith Translation of the scriptures. Joseph B. Noble, a Church member who was introduced to plural marriage in Nauvoo, recorded in 1883 that “the Prophet Joseph Smith told him that the doctrine of celestial marriage was revealed to him while he was engaged on the work of translation of the scriptures, but when the communication was first made the Lord stated that the time for the practice of that principle had not arrived.” [1] W.W. Phelps, another early Church leader, wrote that Joseph received an unrecorded revelation in 1831 commanding the early Saints to take wives from among the Native Americans “in the same manner that Abraham took Hagar and Katurah [Keturah].” [2]

2. Joseph Smith was visited several times by an angel with a drawn sword.

Fragmentary evidence suggests that Joseph Smith may have entered into his first plural marriage with a young woman named Fanny Alger in Kirtland, Ohio. [3]

Very little is known about this marriage, and the relationship ended after Joseph left Kirtland to move to Missouri. After this initial event, Joseph appears not to have taught about plural marriage until the Church was established in its new headquarters in Nauvoo. According to several people close to the Prophet, he hesitated to enter into or initiate any new plural marriages during that time. Helen Mar Kimball recalled, “Had it not been for the fear of His [the Lord’s] displeasure, Joseph would have shrunk from the undertaking.” [4]

More than 20 accounts recorded by witnesses relate that Joseph was visited several times by an angel with a drawn sword commanding him to enter into plural marriage. Lorenzo Snow, Eliza R. Snow, Orson Pratt, Zina Huntington, Helen Mar Kimball, Erastus Snow, Mary Elizabeth Rollins Lightner, Benjamin F. Johnson, and Joseph Lee Robinson all left accounts of the visitation of the angel. [5] Lorenzo Snow related that “in the spring of 1843 he had a long talk with the Prophet Joseph Smith, who fully explained to him the doctrine of plural marriage, and stated that an angel with a drawn sword had visited him and commanded him to go into this principle.” [6]

3. Plural marriage became the subject of wide public debate in the 19th century.

The practice of plural marriage was publicly announced in a sermon given by Orson Pratt in the Salt Lake Tabernacle in 1852. Elder Pratt addressed several concerns about the practice, first teaching that “it is not, as many have supposed, a doctrine embraced by them [the Latter-day Saints] to gratify the carnal lusts and feelings of man; that is not the object of the doctrine.” Elder Pratt taught that plural marriage was a way “by which a numerous and faithful posterity can be raised up, and taught in the principles of righteousness and truth.” Elder Pratt also emphasized that plural marriages were not performed in a random or haphazard way but under the direction of the priesthood as in ancient times. “One man has power to turn the key to inquire of the Lord,” he emphasized, “and to say whether I, or these my brethren, or any of the rest of this congregation, or the Saints upon the whole face of the earth may have this blessing.” [7]

The practice immediately became the source of international controversy and was widely debated, especially in the United States. Mark Twain once joked that he bested a Mormon elder in a debate over polygamy by quoting Matthew 6:24, which reads, “No man can serve two masters.” In reality, a highly publicized debate was held between Elder Orson Pratt and J. P. Newman, the chaplain of the United States Senate. In a verbal sparring match occurring over three days in the Tabernacle in Salt Lake, Elder Pratt matched Newman at every turn as they debated the biblical basis for plural marriage. At the end of the debate, both sides declared victory, though later evaluations favored Elder Pratt’s arguments and skills as a debater. One Catholic writer lamented Newman’s performance, writing that “whatever his qualifications as chaplain of the Senate or his merits as an orator, [he] proved neither a scripture scholar nor an apt debater.” [8]

4. Plural marriage was debated before the United States Supreme Court.

After the public announcement of plural marriage, opposition to the practice was heightened in the United States. At various times in the 1850s, members of both the Republican and the Democratic parties proposed new laws to outlaw the practice. The 1856 Republican platform categorized plural marriage with slavery as the “twin relics of barbarism.” [9]

Latter-day Saints viewed marriage as a religious and not a civil ordinance, feeling an obligation to obey the commandments of God over what they saw as unjust federal interference. Feeling their rights were protected under the First Amendment of the Constitution, Church leaders proposed a test case to prove (or disprove) the legality of new laws Congress had passed against plural marriage. The man asked by President Brigham Young in 1875 to represent the Church was 31-year-old George Reynolds. A modest, unassuming young man, Reynolds had served as a secretary to several prominent Church leaders and had married a second wife only a few months before his case was submitted to the federal courts. Instead of the gentlemanly affair Church leaders were hoping for, the trial soon degenerated into a lurid and exploitative display. A low point came the trials when Reynolds’s second wife, Amelia, then pregnant with their first child, was dragged before the court and forced to testify against her husband.

During the last years of the 1870s, the Reynolds case made its way through several additional difficult trials, eventually being appealed all the way to the Supreme Court. In July 1879, the Supreme Court upheld Reynolds’s conviction. Reynolds willingly submitted himself to spend 18 months living in deplorable conditions in prisons in Nebraska and Utah. Reynolds spent his time in prison preparing the first concordance (an alphabetical list of all the words in a text and the places where each occurs) of the Book of Mormon and was spoken of by his fellow Saints as “a living martyr to the cause of Zion.” [10]

5. The Manifesto was only the beginning of the end of plural marriage.

On October 6, 1890, President Wilford Woodruff issued an official declaration, which has become widely known today as the Manifesto (Official Declaration 2). The Manifesto addressed the United States government when it specified, “We are not teaching polygamy, or plural marriage, nor permitting any person to enter into its practice.” The Manifesto was sustained by common consent and became “authoritative and binding” upon all Church members living in the United States territories.

This move to end plural marriage, however, raised a number of complicated questions. For example, did the Manifesto have any bearing on plural marriages that already existed? President Woodruff explained, “This Manifesto only refers to future marriages, and does not affect past conditions. I did not, I could not, and would not promise that you would desert your wives and children. This you cannot do in honor.” [11]

Some Church members continued to perform plural marriages on a limited basis in Canada and Mexico, where the practice was believed to be legal. Some among the Church hierarchy continued to perform new plural marriages in defiance of the law.

A second manifesto was issued in 1904 by President Joseph F. Smith, which made the solemnization of new plural marriages punishable by excommunication. Two apostles, Matthias Foss Cowley and John W. Taylor, refused to sustain that action and were dropped from the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles in October 1905. [12] Beginning in 1908, President Woodruff’s Manifesto was appended to the Doctrine and Covenants and has been included in every edition since. [13] Within a generation after the Manifesto, the practice of plural marriage was gone, and it remains a fascinating era in the history of the Church.

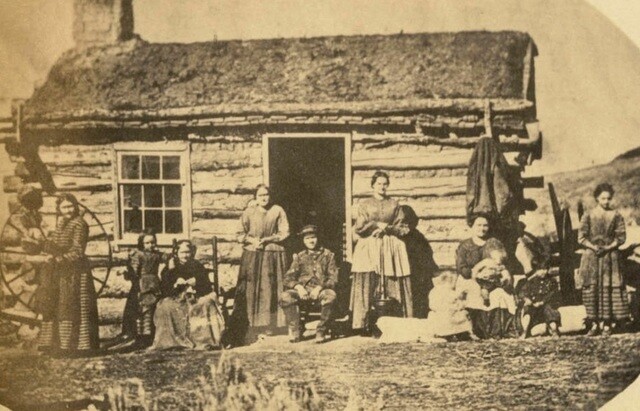

Lead image from Wikimedia Commons

*Footnotes listed below

Learn more about plural marriage and many other fascinating topics in the new book What You Don't Know About the 100 Most Important Events in Church History. Now available at Deseret Book stores and deseretbook.com .

Footnotes:

[1] Brian C. Hales and Laura H. Hales, Joseph Smith’s Polygamy: Toward a Better Understanding (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2015), 31–32.

[2] Ibid.

[3] See “Plural Marriage in Kirtland and Nauvoo,” https://www.lds.org/topics/plural-marriage-in-kirtland-and-nauvoo?lang=eng&old=true (accessed March 24, 2017).

[4] Helen Mar Kimball Whitney, Why We Practice Plural Marriage, 53, quoted in Brian C. Hales, Joseph Smith’s Polygamy, Volume 1: History (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2013), 186. Most of these accounts were recorded in the latter half of the 19th century by Church historians interested in the early history of the practice of plural marriage.

[5] Hales, Joseph Smith’s Polygamy Volume 1: History,188–191.

[6] Heber J. Grant, Diary, April 1, 1896, quoted in Hales, Joseph Smith’s Polygamy, Volume 1: History 188.

[7] Orson Pratt, in Journal of Discourses, 26 vols. (London: Latter-day Saints Book Depot, 1854–86), 1:54, 59–63.

[8] Breck England, The Life and Thought of Orson Pratt (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1985, 245–46.

[9] Sarah Barringer Gordon, The Mormon Question: Polygamy and Constitutional Conflict in Nineteenth-Century America, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 57.

[10] Bruce Van Orden, The Life of George Reynolds, Prisoner for Conscience’ Sake (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992), 87–107.

[11] B. Cameron Hardy, Solemn Covenant: The Mormon Polygamous Passage (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992), 141.

[12] “The Manifesto and the End of Plural Marriage,” Gospel Topics Essay, https://www.lds.org/topics/the-manifesto-and-the-end-of-plural-marriage?lang=eng&old=true, (accessed March 24, 2017).

[13] Richard E. Turley Jr. and William W. Slaughter, How We Got the Doctrine and Covenants (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2012), 105.