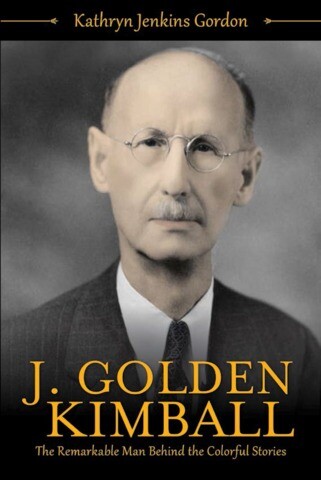

The following is adapted from J. Golden Kimball: The Remarkable Man Behind the Colorful Stories by Kathryn Jenkins Gordan.

J. Golden Kimball is known not so much for what he did but for what he said—and the things he said are characterized by two elements: mild profanity and the tendency to speak his mind. He is, as his great-nephew James N. Kimball puts it, “a reminder that even Saints have sometimes lopsided haloes.”

J. Golden’s language was so colorful that not many people dig any deeper to find out anything else about this enigmatic General Authority. . . But believe it or not, his language is not the only thing about him that was colorful and worth retelling. He was actually a profoundly spiritual, humble, and accomplished man who lived a complicated life marred by financial ruin and deeply hurtful family problems. Perhaps, some have reasoned, his hallmark humor was his way of coping with the things that otherwise would have devastated, maybe even debilitated, him. When one considers the trials he faced, his unwavering service to God and to the Church becomes even more amazing.

Here are four things you may not know about J. Golden Kimball:

1. J. Golden Kimball had 64 brothers and sisters.

His father was Apostle Heber C. Kimball, who begat 64 other children with his plural wives. If you remember your Church history, you’ll remember that Joseph Smith had a rocky go of it when it came to his Quorum of the Twelve. In fact, Heber C. Kimball was one of only two of the original Apostles to never falter when it came to absolute loyalty to the Prophet Joseph; the other was Brigham Young. It stands to reason that J. Golden likely grew up being reminded often of that fact— and his life would become characterized by that same ferocious loyalty. . . .

Someone once asked J. Golden if he believed that Jonah was really swallowed by a whale. Giving it some thought, J. Golden said, “I don’t know. I’ll ask him when I get to heaven.” What if he didn’t make it to heaven?” asked the man. “Then you can ask him,” J. Golden declared.

Even though J. Golden Kimball spent quite a bit of time with his father and was apparently considered by his father to be a favorite son, indications are that the two were not particularly close—at least not what we consider close these days. He may have been one of his father’s favorites, but J. Golden seemed to feel distant from his father. (But give the poor dad a break; we’re talking 65 children.) One sign of a lack of closeness was the way J. Golden talked about his father: most of the time, he quoted what other people said about Heber instead of sharing his own feelings or observations. In speaking at general conference, he particularly liked to quote what Brigham Young and George Q. Cannon said (see James N. Kimball, “J. Golden Kimball: Private Life of a Public Figure,” The Journal of Mormon History, 24:2 (1998), 58).

On one rare occasion, J. Golden did share a personal memory of his father:

“When I was a boy, my father did most of the praying in the home, and when I got to manhood I did not know how to pray. . . . I did not know just how nor what to pray for. In fact, I did not know very much about the Lord . . . and I have been sorry, many times, that I can’t pray like my father did; for he seemed on those occasions to be in personal communication with God. There seemed to be a friendliness between my father and God, and when you heard him pray you would actually think the Lord was right there and that father was talking to him” (Conference Report, Apr. 1913, 86).

Finally, at the age of 77—just eight years before his death—J. Golden opened up to general conference audiences with a stirring tribute to his father’s role and character:

“I honor my father for his faith, courage, and integrity to God the Father and to His Son, Jesus Christ. He was one of the first chosen apostles that never desired the Prophet’s place—his hands never shook, his knees never trembled, and he was true and steadfast to the Church and to the Prophet Joseph Smith. . . .

I take pride in being a son of my father, and as long as I live I shall never fail to honor my father and his successors and try to be as loyal and true and steadfast in the faith as they have been” (Conference Report, Oct. 1930, 60-61).

2. His colorful language was influenced by his experiences working as a mule driver at the age of 15.

[Heber C Kimball’s] death left [his wife] Christeen destitute—at least at first. Heber died intestate, and the settlement was a long, drawn-out, complicated affair. J. Golden summed it up this way:

“Finally, we starved out. Just couldn’t make it. Mother sewed for Z.C.M.I. at those early starvation prices, kept boarders, with poor surroundings and accommodations, as by this time we had been booted out of father’s mansion and lived in a two-room house. Mother went to Brother Brigham repeatedly to secure a position for me, but to no avail. I suppose there were too many others who wanted work. So we were left to hustle for ourselves, and that’s how I became a hustler” [Claude Richards, J. Golden Kimball: The Story of a Unique Personality (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1934, 25)].

Picture this: Christeen, with three kids of her own, lived in a two-room house and kept boarders? Somehow that boggles the mind. As for J. Golden, he faced a dilemma: he was the oldest in his mother’s family, and he felt some responsibility to help support her and his two siblings. Against his mother’s wishes—she begged him to continue his education—he left school and became a mule driver. At the tender age of 15.

J. Golden opened a stake conference address by asking, “How many here have read the seventeenth chapter of Mark in the New Testament?” Most of those in the audience eagerly raised their hands. “Well, there are only sixteen chapters in Mark, and you’re exactly the people I want to talk to today. My talk is on liars and hypocrites.”

Poor Christeen. In the first place, it wasn’t socially acceptable back then for a kid to leave school and work, even in the most dire of circumstances. Young people were urged with every energy imaginable to stay in school and finish their education. And, for crying out loud, a mule driver? Christeen was horrified.

As for J. Golden, he was thrilled; he was able to haul ore from the mines, haul wood from the canyons, and do other daring work with some rough-and-tumble companions who really spiced up the job. He liked being a mule driver and working with the colorful characters who drove the teams. And that, ladies and gentlemen, was his foray into the impressive world of colorful language—really colorful language. As one biographer put it, “A common cliché of the big West was ‘You can’t drive mules if you can’t swear.’ No mule will even wiggle an ear unless he hears a cuss word” (Thomas E. Cheney, The Golden Legacy: A Folk History of J. Golden Kimball (Santa Barbara and Salt Lake City: Peregrine Smith, Inc., 1974), 18).

Christeen, of course, was mortified—and despite her endeavors to get him to consider more elevated employment if he was absolutely determined to work, he resisted her every effort.

3. He refused to be sent home from his mission after experiencing health problems.

If there is one thing J. Golden teaches us, it’s that you can’t keep a good man down. As time went on, his health became progressively worse—something that made him fear he would be sent home from his mission early. It was a justified fear. Here’s what happened when John Morgan, the man who replaced B. H. Roberts as mission president, got a good look at J. Golden:

“I [J. Golden] was still in the office, looking worse than ever. Brother Morgan looked me over carefully. He said, “Brother Kimball, you better go home. The mission is very hard-run for money. It will cost twenty-four dollars to send you home alive, but it will cost three hundred to send you home dead.” It was a matter of business in that office; they had no money. I think maybe that was all I was worth” [Claude Richards, J. Golden Kimball: The Story of a Unique Personality (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1934, 46)].

But J. Golden was having nothing of it. He told the new mission president:

"Brother Morgan, I don’t want to go home. I believe I was called on this mission by revelation; at least they told me so in my blessing. Now God has been good to me and He has been faithful and true; I have tested Him out and if He can’t take care of me, when I have been as faithful as I have, and made the sacrifices I have, then He is not the God of my fathers” [Claude Richards, J. Golden Kimball: The Story of a Unique Personality(Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1934, 46-47)].

The argument worked. President Morgan let J. Golden stay and finish his mission.

One morning as J. Golden and his companion were walking in the Southern States Mission, they encountered a priest. As they approached, the priest sneered, “Good morning, you sons of the devil.” Without skipping a beat and with a smile on his face, J. Golden replied, “Why, good morning . . . father!”

On March 23, 1885, J. Golden was officially released because of his “precarious health” (David Buice, “‘All Alone and None to Cheer Me’: The Southern State Mission Diaries of J. Golden Kimball,” Dialogue, 24:1, 52). It was a few weeks before the exact two-year mark, “but having been in the South now for almost two years, he felt he could return home honorably. In his diary on that day he wrote: ‘This was in accordance with my feelings’” (Ibid).

4. He always injected humor into speeches as a General Authority.

[On] April 8, 1892, while still serving as mission president, J. Golden was ordained one of the seven presidents of the First Council of the Seventy (see James N. Kimball, “J. Golden Kimball: Private Life of a Public Figure,” The Journal of Mormon History, 24:2 (1998), 61) by Apostle Francis M. Lyman. He humorously attributed his calling to his father, saying, “Some people say a person receives a position in this church through revelation, and others say they get it through inspiration, but I say they get it through relation. If I hadn’t been related to Heber C. Kimball, I wouldn’t have been a damn thing in this church” [Paul B. Skousen and Harold K. Moon, Brother Paul’s Mormon Bathroom Reader (Springville, UT: Cedar Fort, 2005), 32].

But don’t let his humor make you think J. Golden had no reverence for his Church callings. Addressing the October 1926 general conference, he said this about receiving a calling:

"We never know how much good we do when we speak in the name of the Lord. I claim that every man fills his niche when he is called of God and set apart and ordained to an office. He may not fill it in the way someone else fills it, but if he is a man of courage he will fill it in his own way, under the influence of the Holy Spirit."

In J. Golden Kimball: The Remarkable Man Behind the Colorful Stories, readers are invited to come to better know this legendary man made famous by his unique humor and powerful testimony. From a chronicle of Kimball’s youthful adventures to the legacy he forged in his more than forty years as a general authority, gear up for a rollicking ride through the life of one of the liveliest servants of the Lord.

Buy now