As the final print volume of the Joseph Smith Papers (JSP) hits the shelves today, there’s no better time to look back and note some of the eye-opening things that the project brought to light over the last 20-plus years. Historians learned, encountered, or confirmed many fascinating details about Joseph Smith and early Church history while working on this immense project. Here are just 12 that come to mind:

1. Joseph and Emma Smith had 11 children, not 12.

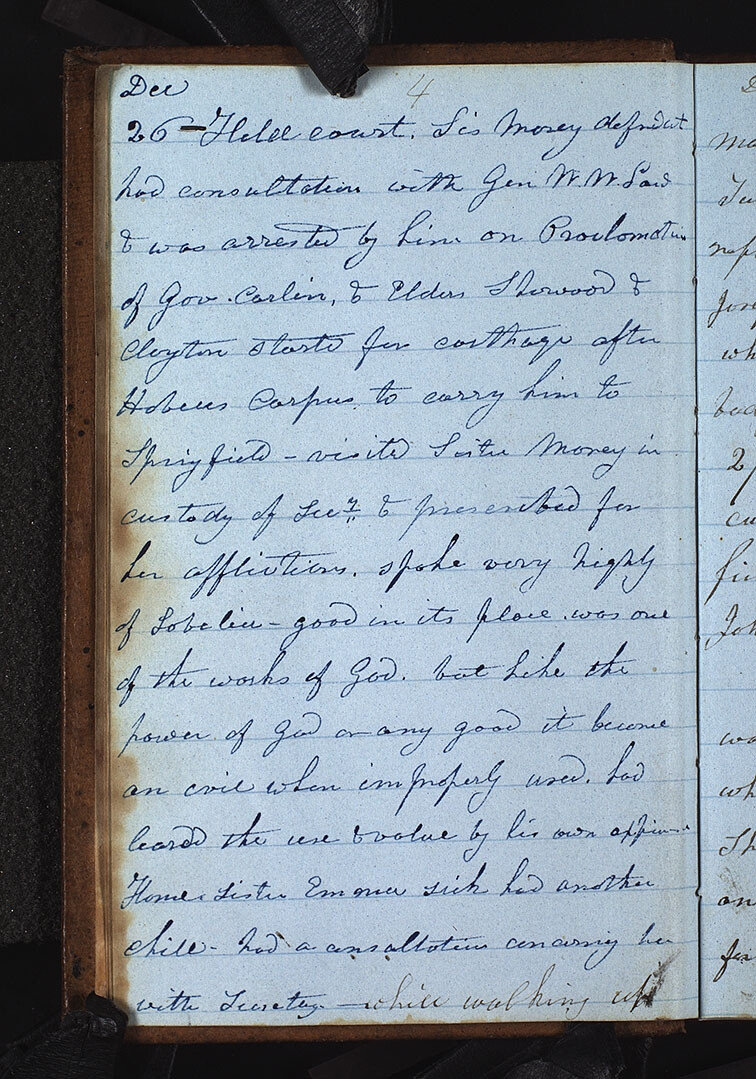

For a long time, it was thought Joseph and Emma had 12 children because of a miscalculation apparently based on a misreading of Willard Richards’s handwriting in the December 26, 1842, entry in Joseph Smith’s journal, for which Richards was the scribe. During the early years of the JSP, historians Andrew Hedges and Alex Smith were comparing the original handwriting in the manuscript to a previously transcribed version, which read “Sister Emma sick had another child.”

“Andy and I were looking at it and thought, ‘That’s not his terminal d,’” recalls Smith, “and then remembered earlier entries over the previous months describing malarial symptoms in Emma.” As they scrutinized the handwriting, Smith and Hedges realized that it actually said Emma “had another chill.”

That misread “child” had been part of the Church’s recorded history for a long time: Willard Richards—who JSP staff members agree usually had notoriously bad handwriting—had used the journal to help compile the Manuscript History of the Church, and he himself had misread the journal entry and written in the history that Emma had a stillborn child in December 1842. B. H. Roberts then carried that error into his History of the Church. “I remember laughing that Richards couldn’t read his own handwriting,” says Alex Smith.

Correcting “child” to “chill” is just one of many such text corrections made during the rigorous manuscript verification process that historians perform on every document.

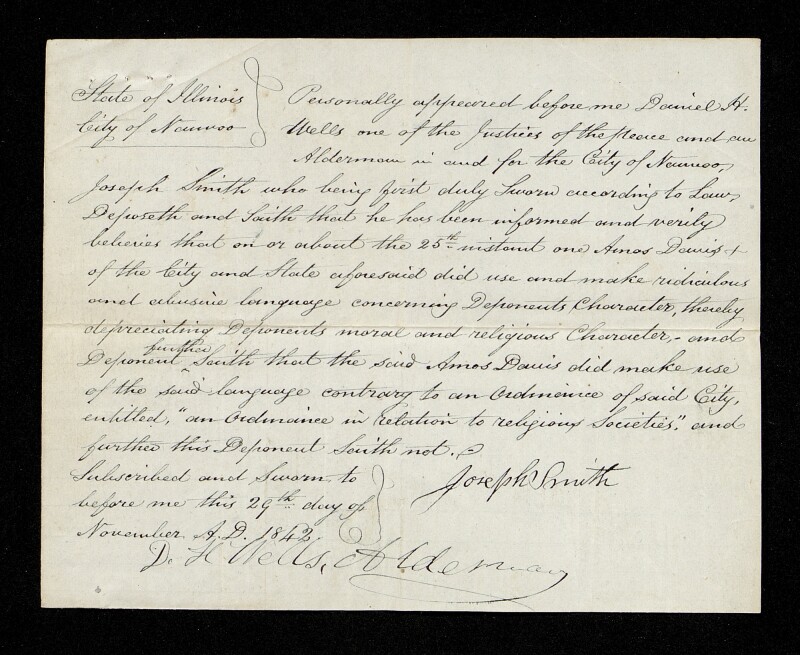

2. Joseph Smith was involved in around 200 legal cases.

When the JSP team first started organizing legal cases, they estimated that Joseph Smith had been a party to about 50 cases. They soon realized that estimate was far too low, and the project now places the number at around 200 cases in which Joseph was a plaintiff, defendant, witness, or judge.1 Starting in 2015, the project began publishing the Legal Records series on the JSP website, with the anticipated completion of the series scheduled for January 2024.

"The Legal series is built on decades of research by historians, lawyers, and archivists who spent countless hours scouring courthouses and repositories for cases involving Joseph Smith,” explains David Grua, the lead historian of the series. “It has been amazing to see all that work come to fruition with the digital publication of the Legal series.”

Even with all the work that has already been done on Joseph Smith’s legal cases, new material continues to come to light. For example, Missouri archivists, working with local Church members, found a previously unknown case brought by Joseph Smith in the St. Louis Circuit Court, and the JSP was able to publish those documents from the Joseph Smith v. Marshall Brotherton case online in 2022.

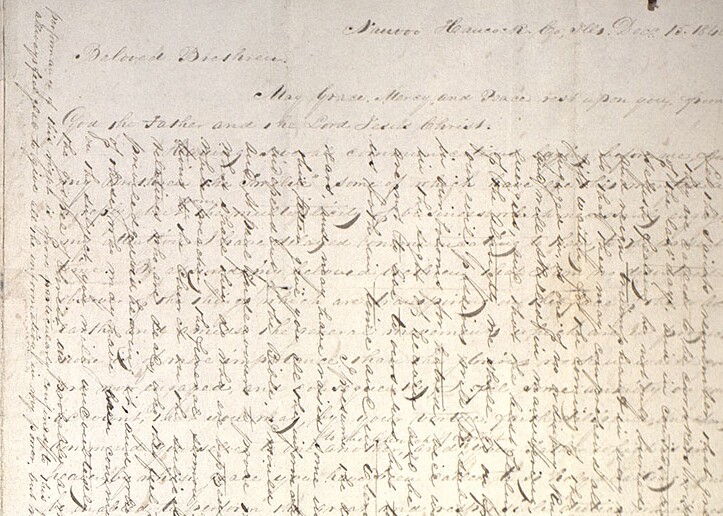

3. The early Saints were into reducing, reusing, and recycling before it was cool.

Some of the things we’ve learned are related to the physical traits of the documents rather than their contents. For example, physical evidence helps us see the Saints were extremely thrifty with their paper resources. One practice involved saving paper by writing horizontally across the page and then rotating the page to write vertically across the previously written text in a crosshatched pattern, as in this letter of December 15, 1840, from Joseph Smith to the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. Another common practice involved having multiple writers take turns writing their messages in a single letter, as in this intriguing February 1841 letter to Emma Smith’s brother David Hale, which contains the handwriting of Emma’s nephew Lorenzo D. Wasson, as well as that of Joseph and Emma Smith. The early Saints also reused their paper resources when they could, and we have several records handwritten on the back of previously printed documents, like this October 1840 Instruction on Priesthood written on the back of old Kirtland Safety Society forms.

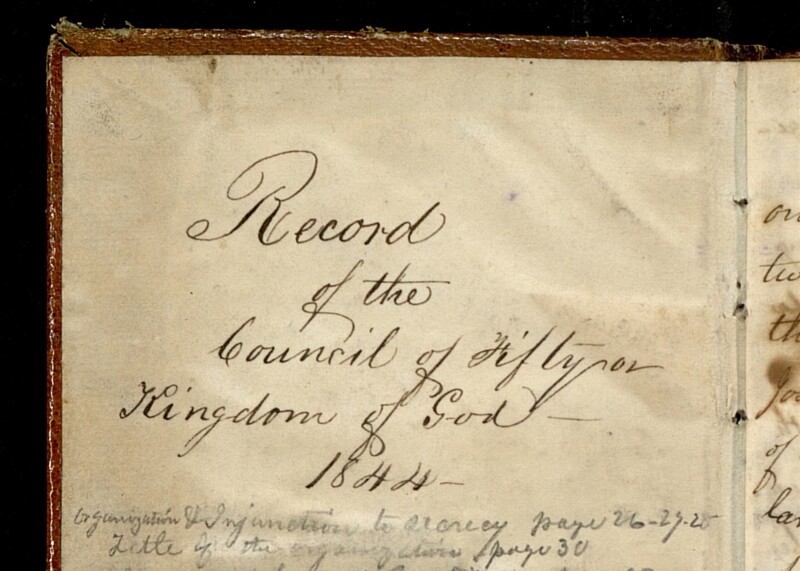

4. Publishing the previously unavailable Council of Fifty minutes ended speculation about what they contained.

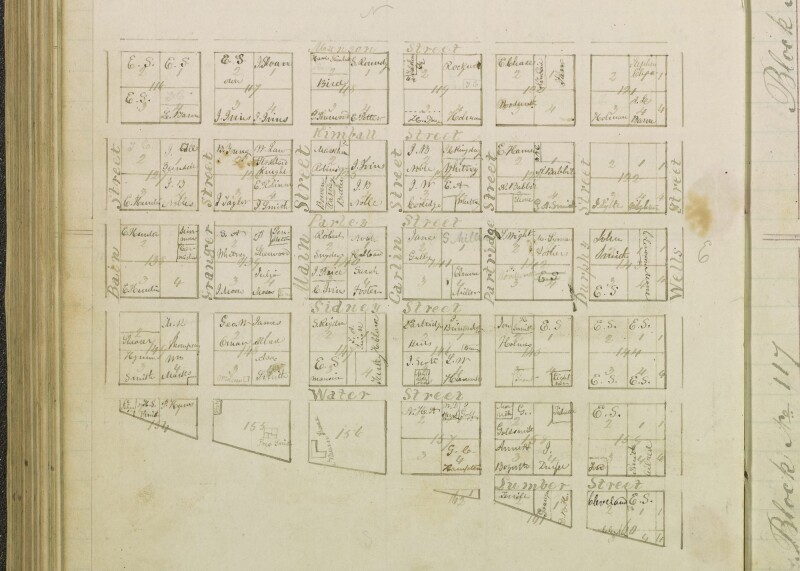

For decades, historians had known about the minutes of the Council of Fifty, an organization that Joseph Smith formed near the end of his life. Because the records had been closed to research, speculation about their contents ranged from the outlandish (treason! a coronation!) to the mundane. In a thrilling development for the JSP team, these minutes were transferred from the Office of the First Presidency to the Church History Library in 2010. A short time later, the First Presidency gave the JSP permission to publish the minutes. The minutes were published in 2016 in the project’s Administrative Records series. Regarding this publication, JSP historian Mark Ashurst-McGee said, “Access to and publication of the Council of Fifty minutes put to rest the wildest claims about what these records might hold. More importantly, it provides loads of new information on the late Nauvoo period.”

What did we learn from the minutes? The Council of Fifty (so named because it was made up of approximately 50 men) played an important role in the late Nauvoo era. The council was essentially designed as a political body that would protect the Church and allow it to flourish. At the practical level, the council had probably three main accomplishments: it helped manage Joseph Smith’s campaign for United States president; it provided a type of government in Nauvoo after the Nauvoo city charter was revoked by the Illinois legislature; and it played a major role in exploring possible settlement sites and in planning the Church’s migration to the West.

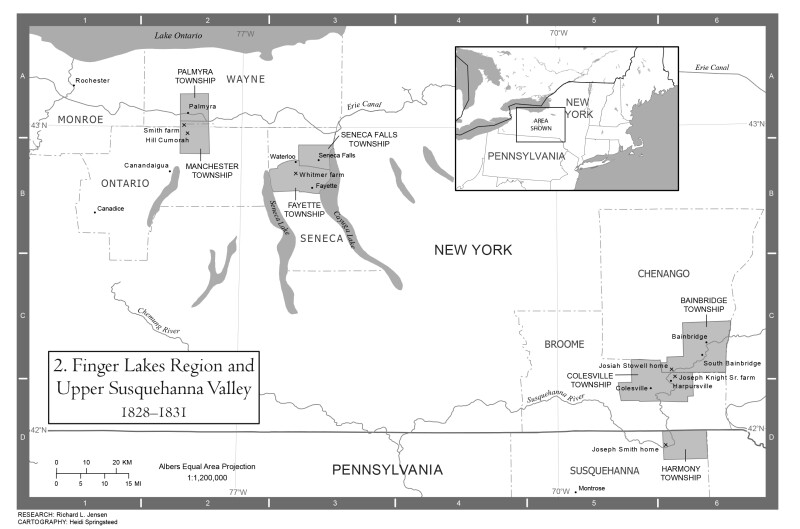

5. The Church’s founding meeting was held in Fayette, not Manchester, New York.

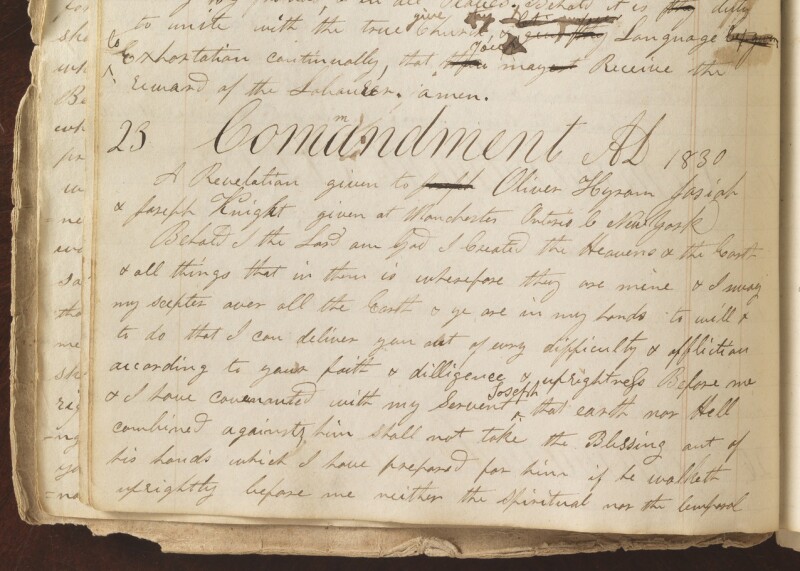

This fact might seem obvious, but because of conflicting evidence in the existing records, historians have long debated whether the Church’s founding meeting was held in Fayette or Manchester, New York. The question existed partly because the earliest extant manuscript of the revelation given at the founding of the Church on April 6, 1830, was not available until relatively recently.

That earliest manuscript had been in the custody of Joseph Fielding Smith for years while he acted in the office of Church historian and recorder (from 1921 to 1970). When he became President of the Church in 1970, those records moved with him to the Office of the First Presidency and were generally unavailable to researchers. But in 2005, the First Presidency transferred custody of the Book of Commandments and Revelations, also called Revelation Book 1, to the Church History Library. When JSP historians were finally able to examine this early record of Joseph Smith’s revelations, they discovered that the manuscript clearly stated the meeting was held in Fayette, Seneca County, New York. The manuscript, found in Revelation Book 1, has now been published as part of the JSP.

6. Historians acquired text for two revelations they knew existed but had never read, as well as several new sermons.

Access to the previously unavailable Revelation Book 1 allowed historians to pin down the text for two revelations that had been mentioned in the historical record but had never been published or transcribed. Revelation Book 1 contains the only known versions of an early 1830 revelation dealing with securing a copyright of the Book of Mormon in Canada and a March 1832 revelation titled “Sample of Pure Language.” The Council of Fifty minutes contain the only known versions of several sermons from Joseph Smith, such as an April 11, 1844, discourse he gave about intolerance and religious liberty. Joseph was apparently so animated during this discourse that he snapped a two-foot ruler in half.

7. Joseph Smith was generous, almost to a fault.

Many of Joseph Smith’s financial records have been neglected by researchers, and it’s easy to understand why invoices, deeds, promissory notes, and ledgers full of numbers and names were overlooked in favor of other seemingly more exciting documents. But the JSP is publishing all these records in the Financial Records series on the JSP website, and historians are finding that they provide an abundance of relevant and fascinating information.

Elizabeth Kuehn, lead historian of the series, reports that one of her favorite findings has been Joseph Smith’s generosity, which reveals itself clearly in his financial records. “In the Trustee Land Books, we have irrefutable proof that Joseph essentially gave away significant amounts of land to widows and impoverished Saints, leaving him on the hook for the bill because he never asked them for payment,” explains Kuehn. Joseph Smith is not known for being a successful businessman, and his tendency toward generosity certainly wouldn’t have helped his business ventures. Though most people tend to focus on the failure of the Kirtland Safety Society as evidence for Joseph’s lack of business acumen, the financial records give us a more balanced view of his financial activities.

8. The British Saints donated even more than we thought to the Nauvoo Temple construction.

While researching documents for the JSP Financial series, Elizabeth Kuehn and her team examined tithing records (kept in the Book of the Law of the Lord) and found that hundreds of British Saints were listed by name as paying tithing or making donations toward building the Nauvoo temple—more than previous researchers had thought. A significant number of donations came from Manchester, Tottington, Bolton, and other branches in England, with additional donations from branches in Edinburgh and Glasgow, Scotland. “The breadth of donations coming from the Saints in Great Britain is staggering and an important contribution to the Church’s finances and ability to complete the temple,” says Kuehn. “It’s inspiring to see these Saints who lived thousands of miles away from Nauvoo donating to the temple, knowing that they might never be able to enter its doors themselves.”

9. The revelation canonized as Doctrine and Covenants 49 was received on May 7, 1831, not March 1831.

The revelation directing Sidney Rigdon, Parley P. Pratt, and Leman Copley to preach to a Shaker congregation eighteen miles away from Kirtland, Ohio, had been erroneously dated to March 1831 in early editions of the Doctrine and Covenants, and the error continued until the 2013 edition corrected it to May 7, 1831. The difference of a couple months may not seem significant, but when we learn that Rigdon and Copley arrived in the Shaker community that same evening of May 7, with Pratt arriving the next day, it becomes an inspiring lesson in prompt obedience. This small correction is just one representative of many such clarifications, improvements, or corrections to the introduction, Chronological Order of Contents, and section headings of the 2013 edition of the Doctrine and Covenants based on information gleaned from the JSP.

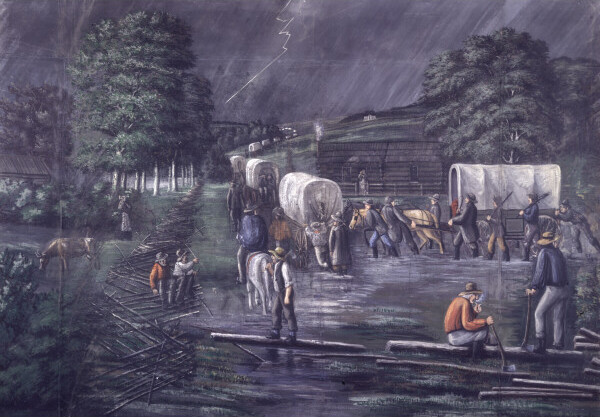

10. Joseph Smith’s expedition from Ohio to Missouri in 1834 wasn’t actually called “Zion’s Camp” at the time.

Documentary evidence from the JSP reveals that the actual name was “Camp of Israel.” The name “Zion’s Camp” didn’t enter Latter-day Saint vernacular until the mid-1840s. Additionally, many people (then and now) assumed that the purpose of the expedition was to forcibly take back the land the Saints had been driven from in Jackson County, Missouri, but documents published by the JSP show something different. Expedition members were directed to wait for the governor to muster a portion of the state militia, which they hoped would escort the Saints back into Jackson County. After the militia was discharged, the volunteers were to remain in Missouri, protect the Saints from any future attacks, and help plant crops. Unfortunately, the governor refused to call out the militia, and these plans never materialized; the Camp of Israel was disbanded after about two months.

11. Joseph Smith’s aspirations in visiting President Martin Van Buren were likely humbler than many people think.

In December 1839, Joseph Smith and Elias Higbee met with Martin Van Buren, president of the United States, to ask him to help the Saints with their losses and persecution in Missouri. It is unclear what exactly they asked of him, but some have thought they possibly requested an executive order to force redress and reparations for Church members’ losses; however, no documentary evidence exists to support this possibility. Based on December 1839 letters to Seymour Brunson and the Nauvoo High Council and from Robert D. Foster, it appears that their request was not about obtaining an executive order but rather a hope that the president would strengthen the Church’s petition for redress to Congress by mentioning the Saints in his annual address to Congress (now known as the State of the Union address). Whatever the request was, we do know with certainty that Van Buren refused it.

12. We know what the carpet looked like in Joseph and Emma Smith’s home in Kirtland.

A document from the JSP Financial series has given us some insight into what the Smith family home in Kirtland looked like. An October 1836 invoice includes the purchase of “Plaid Venetian” carpet for the Kirtland Temple. Mark Staker, master curator in the Church’s Historic Sites Division, is currently working on restoring the Smiths’ Kirtland home, and he explains, “Since the home was largely furnished through the same purchases, we believe we know what the carpet looked like in the Smith home as a result of that document.” Staker has worked with textile experts to recreate this colorful, common weave of the time, and it will be featured in the restored home. Staker also reports that store ledgers from the Financial series contain details that have helped Historic Sites staff decide on furnishings for the Smith home.

![IMG_6229[6947].JPG](https://cdn.ldsliving.com/dims4/default/b5cce84/2147483647/strip/true/crop/5184x3456+0+0/resize/800x533!/format/jpg/quality/90/?url=http%3A%2F%2Flds-living-brightspot-us-east-2.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com%2Fed%2F7b%2F0b8cc687463981d6f212e70a3572%2Fimg-62296947.JPG)

We’re not done yet.

Even though the last print volume of the Joseph Smith Papers is on shelves as of June 27, 2023, there is still work to be done. The 27 print volumes represent only a fraction of the documents found in the Joseph Smith Papers—hundreds more documents that couldn’t fit into the volumes can be found on the Joseph Smith Papers website. The website will continue to grow as the digital-only Financial series and Legal series are completed in the next couple years. And who knows? Perhaps more documents will turn up (much like that newly discovered Smith v. Brotherton case mentioned earlier). If they do, experts in Joseph Smith’s history will be eager and well prepared to examine, transcribe, annotate, and publish them so we can learn more about Joseph as a person and appreciate how the Lord used him to help restore the gospel of Jesus Christ.

The Joseph Smith Papers

Notes

1. See Sustaining the Law: Joseph Smith's Legal Encounters, edited by Gordon A. Madsen, Jeffrey N. Walker, and John W. Welch (Provo, Utah: BYU Studies, 2014), vi.