Though it's the primary language of the United States, English is notoriously difficult to learn. And despite having fewer native speakers than both Mandarin and Spanish, it's the most widely spoken language in the entire world—which means lots of people have had to learn it. It's a challenging task for all who undertake it, and that was the problem Brigham Young hoped to solve when he ordered that the board of regents at the University of Deseret (now the University of Utah) create a new alphabet.

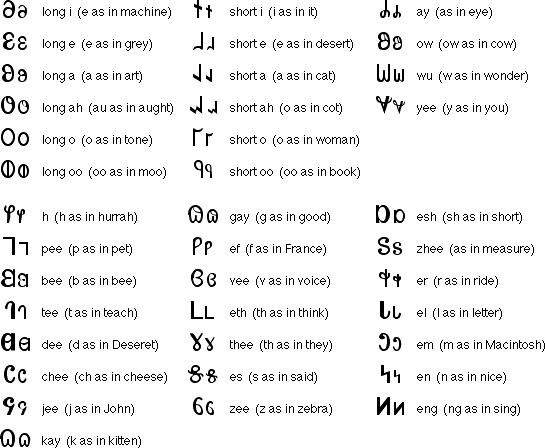

The "Deseret Alphabet," as it's commonly called, was primarily developed by George D. Watt (a local language expert) and Parley P. Pratt. Also working on the committee were Heber C. Kimball, Orson Pratt, and Wilford Woodruff, among others. Upon the alphabet's completion in 1854, President Young prescribed it to the school system, saying, "It will be the means of introducing uniformity in our orthography [the spelling system of a language], and the years that are now required to learn to read and spell can be devoted to other studies."

Photo from World Language Process

President Young's ultimate goal was to replace the traditional alphabet with a more phonetically correct version. He claimed that immigrants would have an easier time learning this alphabet than learning to read and write in English, in which the spelling is often phonetically inconsistent. Though undertaking such a feat seems unusual to us today, similar experiments were not uncommon during this time period. Ronald Kinglsey Road created the most well-known example—the Shavian alphabet—which contained 48 characters that were even more simplistic than those created at Deseret.

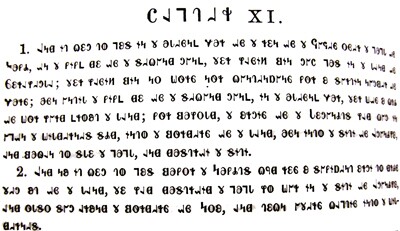

The Book of Mormon was published in the new alphabet, as were several other books. The Deseret News would also frequently publish various passages from the New Testament in the alphabet.

The alphabet was discontinued soon after Brigham Young's death, in part due to excessive costs. Pratt estimated that printing a regular library in the characters would cost well over a million dollars. However, though the alphabet was never widely adopted, evidence of it still exists. Hobbyists and self-publishers have begun to publish new volumes in the language and continue to study its role in early Church culture. Perhaps the most notable historic example, however, is a gravestone replica in Cedar City, where the original marker was engraved in the characters of the Deseret alphabet.

Photos from Deseret Alphabet Blogspot