On November 14-18, 2017, the Baja 1000 motorsports race hosted its 50th-anniversary event. Nineteen riders signed up to race in the Ironman class as motorcyclists. Only five finished.

When Wayne Schlosser set out to complete the Baja 1000, he left heartfelt notes to his wife and daughters, just in case he didn’t come back.

The Baja 1000, the Mount Everest of off-road motor racing, is a dusty, high-speed race down the Baja Peninsula in Mexico. And every year, people are killed. Especially the motorcyclists.

So why would Schlosser, a husband, father of four, and not a professional motorsports athlete, decide to enter the Ironman class and ride a motorcycle solo 1134 miles across the desert?

Schlosser grew up watching the race on TV with his dad as a young boy. In college, he and a few buddies planned to do the race together but didn't even make the drive to the starting line.

Then, when it was announced that the Baja 1000 would celebrate its 50th anniversary with a longer course of just over 1100 miles, Schlosser couldn't help but connect the distance with that of the Mormon pioneers. He'd been serving as a family history consultant in his ward, and his pioneer ancestry was often on his mind.

As Schlosser began thinking about it, he saw many parallels between the journey of Mormon pioneers and this race. Of course, he could never experience their journey in quite the same way, but he felt compelled to do his own trek in their honor.

“It was the same distance, the same terrain. Even though I was pushing a motorcycle and they were pushing a handcart, they had three months, and I had three days,” Schlosser said.

No one thought he would make it.

Preparation and Training

All of Schlosser’s motorsports buddies kept telling him, “You need to ride more,” but Schlosser just brushed off their comments. He wasn’t in this to win it, he reasoned. At 48 years old, his goal was just to finish.

Schlosser did cross-fit three or four times a week to improve his overall physical fitness. “Wayne, there are certain muscles that you use when riding,” his friends would beg. “You have to ride.”

But that wasn’t part of Schlosser’s journey. The way he saw it, the pioneers didn’t “train” before they crossed the plains. The farmers, he reasoned, might have been in pretty decent shape, but not the cobblers, the tailors, or the printers.

“If you can imagine 200 years ago . . . a wife telling her husband, ‘Bob, you better get out there and start pushing a handcart around, because next month when we leave you’re going to be sore,’ What’s he going to do, push the cart to the mailbox and back? He probably did it a few times, put some bags of flour in the handcart and went to town, but I mean, can you just imagine somebody working out with a handcart?”

When it came time to start the race, the odometer on Schlosser’s 2015 KTM 350 XCWF motorcycle read only 220 miles. “Everyone thought it was comical that I was going to do this,” Schlosser said.

Leaving Loved Ones

Schlosser’s wife and daughters cried when he left. They knew it was a dangerous race, and none of them wanted him to go. “Please dad, what if we don’t see you again?” his daughters asked.

Although Schlosser was confident he would return, the experience touched him. It brought to his heart a taste of how difficult it must have been for his ancestors to leave friends and family behind when they began their journey west. “You can imagine how many tearful exchanges there were," he said.

Schlosser's wife and four daughters. (Image courtesy of Wayne Schlosser)

Schlosser comforted his family by saying that he was more likely to get killed in an automobile accident on the freeway than in this race. “You can’t live your life afraid of what might happen. You just have to live your life with the faith that you’re doing the right thing and you’ll be protected along the way," he said.

He wrote them letters, hoping to explain why he felt compelled to complete the race. He wanted them to understand that he was riding with a purpose. “I didn’t want them to think I was just a crazy guy going off on a motorcycle race.”

At the Starting Line

Most race the Baja 1000 in teams, switching out drivers along the way and competing in large, 6,000-pound trucks dubbed “trophy trucks.” These million-dollar trucks are followed by extensive support crews that offer repairs, extra tires, and additional team members. Many have factory sponsors that trail them in helicopters.

A "trophy truck" at the Baja 1000. (Image from YouTube)

Even those who are crazy enough to race in the Ironman class as motorcyclists definitely don’t go at it alone. They, too, have a support crew to assist them along the way. It’s not uncommon for a motorcyclist in such a race to have to swap out their tires six or seven times.

But not Schlosser. He had no extra tires and no support crew. He had planned 18 pit stops along the course at which he would fill up on gas. He had a few runner’s Gu packets, granola bars, and waters stored in backpacks stashed at each of these points, but other than that, he’d be depending on the generosity of the Mexican race fans for food.

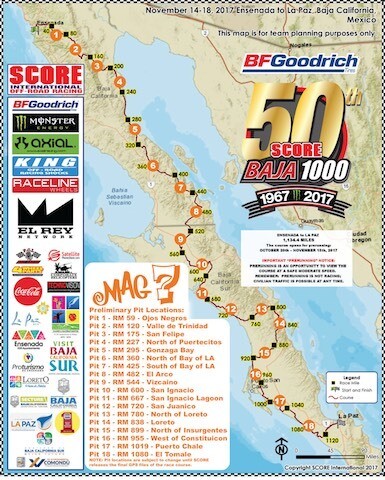

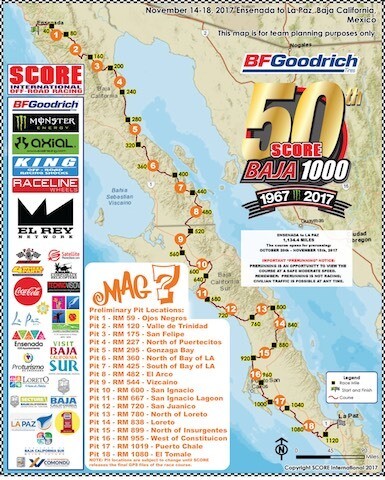

The course was set in the middle of the Mexican desert—a long dirt road cut into the landscape about two feet deep, with thick cacti littered on either side. It consisted of 37 water crossings, one of which was a creek four-feet deep, and ran from Ensenada to La Paz.

The 50th Anniversary Baja 1000 race course map. (Image courtesy of Wayne Schlosser)

Mexican fans would camp out along the course. In many ways, the Baja 1000 is their Running of the Bulls. Not only did they cheer on the racers and offer a campfire and a bit of food at various points along the road, but they would stand in the path of a trophy truck and jump out of the way at the last second to show their bravery.

It was midnight when Schlosser pulled into the starting arena and revved toward the white line. He had a stomachache from the armadillo tacos he’d eaten the night before. The race announcer boomed, “The Ironmen, they’re different animals. You gotta be tough to come down here.”

Schlosser at the starting line. (Image from YouTube)

Let the Race Begin

The previous year seven riders competed in the Ironman class. Only two of them finished. It wasn’t until mile 475 that Schlosser truly began to experience why that was.

In the Baja 1000, the trophy trucks start nine hours behind the motorcyclists in order to allow the bikers a head start. Sounds like a courteous race gesture, except that the trophy trucks catch up, and when they do, motorcyclists often get run over.

Schlosser was filling up on gas when he heard the sound of an engine in the distance. All of a sudden, the first trophy truck blazed past the camp at 100 mph, whipping up a wave of dust so thick that Schlosser couldn’t see his hand in front of his face.

The kind of dust kicked up by a trophy truck. (Image courtesy of Wayne Schlosser)

About 30 seconds later, a motorcycle came through the dust with his headlights on. He got off his bike. “That guy almost hit me!” he yelled. Moments later, a second trophy truck came blazing through the dust. With the thickness of the filthy air, the driver of this second truck was relying solely on a navigation screen to stay on course.

The people in the camp gathered around the motorcyclist, murmuring how lucky he was that he hadn’t been behind the second truck. If the first truck had barely missed him, the second truck, which couldn’t see anything, surely would have taken him out.

“That’s it. I’m out,” the motorcyclist said. “This is crazy.”

I have to get back out there, Schlosser thought. He listened for the sound of a third truck, but when he heard nothing, he pulled out. He had a 40-mile stretch before the next stop. He went “as fast as humanly possible” and “could not see a thing.” He relied on the tire tracks of the trucks to stay on the road. This was one of two or three times in his life when he thought he might actually die.

Miraculously, he made it to the next stop before any other trophy trucks came through. He began to realize that although he’d known the race would be dangerous, he hadn’t really known quite what he was getting himself into. He believes it was the same way for the early Saints.

Continuing the Journey

At mile 805, Schlosser stopped. It was 91 degrees, and he was overheated. He ripped off a few layers and pulled out his SAT phone and tried to call his wife. “I just needed some encouragement,” he said.

Schlosser, at a pit stop during the race.

After five tries, he finally got through. He started crying. “This is so hard. It’s harder than I thought it would be. I just can’t do it,” he said.

“Just one more mile,” his wife said. “One more mile. You can do it. You’re almost there.”

The connection dropped, and Schlosser fell to his knees in the dry creek bed and started praying. “I started blubbering like a baby. I mean, I was blowing snot out of my nose. I was praying out loud and I could hardly even talk.

“I was telling Heavenly Father, ‘I do not want to quit, but I truly cannot go one more step,’” Schlosser said. He didn’t want to turn back, but even if he did, there was nowhere to turn back to.

As he prayed, an impression came over him. He realized that God had made him “equal to the task.” He had made his equipment last; He had made him better than his surroundings. And now I'm finally broken, Schlosser thought.

In his mind’s eye, he could see a husband and wife kneeling over a grave on the Mormon pioneer trail. They were spent. They’d been walking for two months and had lost loved ones. The journey was harder than they could have ever imagined.

“This feeling came to me that this is the sacrifice. You had to give all you had, and now, to truly understand what they went through, you have to be broken down of everything you thought you were. And now, if you decide to keep going . . . I will finish the journey for you.”

Schlosser got up, put his stuff on, and straddled his bike. He didn’t feel rejuvenated, but he felt like he could go on. A few miles later he found another Ironman laying on the road, waiting for his crew to come pick him up. As Schlosser passed, he remembered thinking how lucky he was that he had faith in the journey. He knew he would make it.

The Stormin’ Mormon

Schlosser crossed the finish line at 52 hours and 33 minutes. In all, he’d slept for just three 20-minute naps and didn’t change his tires once.

“It’s just not conceivable that one set of tires without repairs could make it that distance,” said Schlosser’s friend Brad Giles. “Most teams on a motorcycle would plan to replace both the front and rear tires multiple times.”

Left: Schlosser holding his finisher's medal. Right: "Stormin' Mormon" painted with Schlosser's race number on the front of his motorcycle.

“I just kept my shoulder to the wheel and kept going,” Schlosser told the interviewer.

“Would I want to do it again?” Schlosser asked himself. “Absolutely not. It was the hardest thing I ever did.”

But, he also wouldn’t trade the experience. He said that in his darkest hour, he knew that Heavenly Father put everything else on hold to listen to his prayer and offer help. He learned what it meant to truly give all he had, to be completely stripped of pride, and then to let God do the rest.

“It was the coolest experience . . . to have Heavenly Father teach you a lesson, and have a way to increase your faith and your relationship with Him. It was the most amazing experience ever.”

You can also watch video footage of Schlosser's race:

Lead image courtesy of Wayne Schlosser.