Warning: This article contains some war content that might be disturbing for some readers.

When my father, Alfred R. Young, was liberated from a Japanese POW camp at the end of World War II, he weighed 90 pounds—scrawny for any man, but skeletal for someone 6-feet 3-inches tall. His weight, however, was only a shadow of concern compared to his mental and emotional condition after 39 months of wartime captivity. He endured two hellship voyages; physical, mental, and emotional starvation; innumerable beatings; forced labor; disease, psychological abuse; isolation; and six months of Allied bombing raids that eventually obliterated his prison camp, devastated Tokyo and Yokohama, and killed many of the men who had become his brothers.

His physical internment ended in 1945, but Dad was still a captive almost eight years later when I was born. I knew he was a captive because I could see he was somewhere else, walled up inside the sternness of his countenance. I knew it because I could see emptiness in the depths of his eyes.

I came to know that the darkness had something to do with the Samurai sword in the shadows under the couch in the living room and battered cardboard boxes in the garage that were filled with letters, papers, and colorless photographs of desolate places and doleful men.

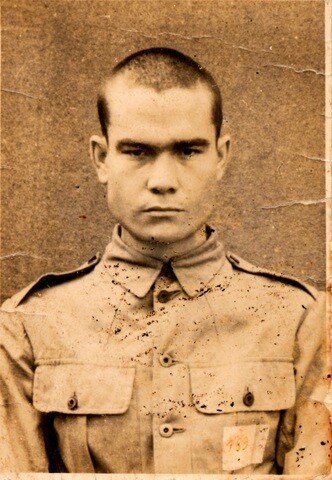

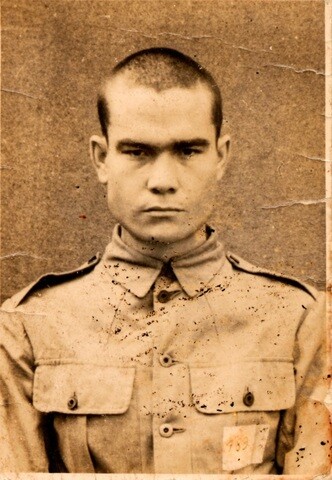

One of those pictures was a close-up of a man, completely alone, whose eyes were so deeply set that sunlight could not reach them. I can still remember my amazement upon learning that the man in the picture was my father.

Alfred R. Young’s Kawasaki Camp 2B prisoner photograph taken July 10, 1943. Image courtesy of Al R. Young.

The First Attacks

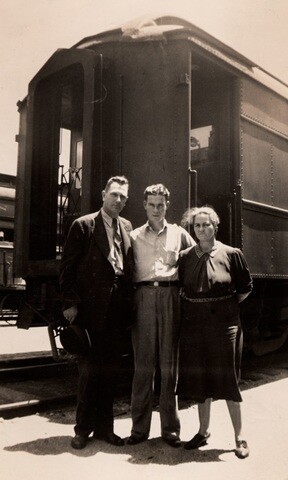

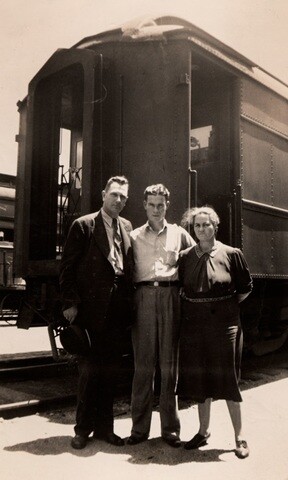

In 1939, the sunlight in some of the pictures shone bright upon my father and his parents as they stood at a railway station. Dad had enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps and was bound for Fort McDowell near San Francisco. From there, he was sent to Clark Field—an air base on Luzon island in the Philippines.

Pop, Alfred and Mom say goodbye at the railroad station in Oklahoma City before Alfred leaves for Fort McDowell and then for Clark Field on the island of Luzon in the Philippines. May 20, 1939. Image courtesy of Al R. Young.

Dad’s enlistment required only two years of duty overseas, but by 1941, the U.S. was preparing for war and his return to the States was canceled. Consequently, on December 8, 1941, just hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Dad endured the terrible destruction that swept over Clark Field, doing to the United States’ air power in the Pacific what had just been done to its navy. Before the war was two days old for American soldiers, Dad had lost two bombers and was the sole survivor of his crew.

Clark Field after the attack, December 8, 1941. Image courtesy of Al R. Young. Image courtesy of Al R. Young.

He remained at Clark Field until the Imperial ground assault on the Philippines forced an evacuation. Christmas 1941 found him in a foxhole on an island named Bataan. In the dead of night, his outfit was split up and he was assigned to a group that boarded an inner island cruiser. Traveling only by night, they threaded their way southward among the islands, survived a direct aerial bombing attack, and disembarked on the island of Mindanao, where he was assigned to a machine gun post on the Pulangi River among the iguanas and head hunters.

For four months, he watched planeload after planeload of American officers and men evacuating from the Del Monte Air Field just a few miles to the north. As a bombardier, he should have been aboard, but the call never came. One morning, he and his men awoke to discover that their officers had vanished in the night. Those left behind survived on worm-infested rice, lived off the land, traded with the Moro people, and eventually retreated into the hills.

Life as a Prisoner

Alfred R. Young poses in his flight gear in front of a Martin B-10 B, in which he flew as a bombardier before the war. The photo was taken circa 1940. Image courtesy of Al R. Young.

When his command surrendered in May 1942, my dad passed through the gate of a makeshift prison camp at Malaybalay. From there, he was among prisoners loaded into what would become known as a hellship, which took them to Manila’s infamous Bilibid Prison. From Bilibid, he and thousands of other prisoners were loaded into unmarked freighters bound for hard labor in Japan to drive the Imperial machinery of war.

Climbing down the metal ladders into the dark holds of those ships, prisoners were forced at rifle butt onto cargo shelves where they crawled in darkness toward the bulkhead. Dad descended until nothing but the naked rivets and rough joinery of the hull separated him from the murky waters of Manila Bay. In the deep shadows, he crawled through the prisoners, already packed into the hold like bodies without coffins, until he came to the small wedge of a space where the curvature of the hull met the underside of a cargo shelf. The hatch closed. Darkness swallowed him.

Cradled in cold steel and stifling stench, groaning men with dysentery and other diseases lived and died in their own waste. It was impossible to know whether the shadowy forms around him were still men or corpses. The only reprieve was waiting on deck in the long lines for the over-the-side latrines that had to serve nearly 2,000 prisoners.

Because the freighters were unmarked, during their journey they came under Allied submarine attack. Dad watched with the rest of the men in line for the latrines, none of whom had a life jacket, as the captain tried to out-maneuver white tufted torpedo trails that claimed more than 3,000 prisoners. Fortunately, Dad’s ship escaped such a fate.

Dad was sent to a labor camp on the island of Kawasaki in Yokohama’s waterfront industrial area. There, he endured days of disease, deprivation, starvation, forced labor, humiliation, beatings, and the constant threat of death for more than three years.

Kawasaki Camp 2B prisoner-group photograph taken November 12, 1943. Image courtesy of Al R. Young.

The Hope Found in a New Book

Reading material in the camp was scarce. He read Robin Hood so many times he never wanted to see it again. Commenting one day to a fellow prisoner about how glad he would be for anything new to read, Jim Nelson, a young man from Utah, said he had a book he would gladly loan to him—but it was about religion. Dad exclaimed that he was desperate enough to read anything.

With the book in hand, Dad took it to the mat where he slept, sat down cross-legged under his blanket, and began his first reading of the Book of Mormon. Much to his delight, it was not a book about religion—it was a story.

In fact, it was a story about a family—and memories of family and childhood were something that had already saved Dad’s life through the long ordeal of captivity. Whether it was enduring the dreariness of meaningless labor or surviving the kicks and fists of his captors, he escaped into his memories of home, and in the Book of Mormon he found himself suddenly in a family with a bunch of rough and rowdy kids who acted just like his five brothers and two sisters.

Before the story was 10 pages old, the neighbors had tried to kill the father; the family had left home, wealth, and comfort behind to cross a wilderness; and the boys were swept up in a quest. And it was an exciting one that resulted in theft of the family fortune, assault and battery on the youngest brother, the beheading of a corrupt military commander, subterfuge (complete with costume), kidnapping a servant, and smuggling a priceless treasure out of town in the dead of night. Whether or not the book had any religious significance, it was one walloping good tale!

After completing the Book of Mormon, Dad asked if there were other books like it that Jim would let him read. Jim admitted he had another book, but he really didn’t think Dad would like it. Dad pleaded, however, and excitedly returned to his mat and his blanket to lose himself once again, this time in the pages of something called the Doctrine and Covenants. When he finally finished, Jim wanted to know what Dad thought. Dad replied thoughtfully: “It’s very well-written, but the plot is lousy.”

Liberation at Last

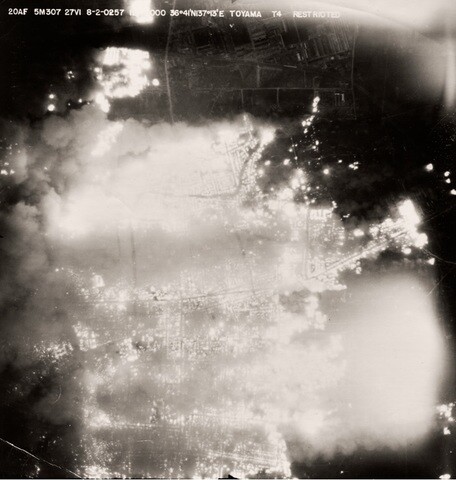

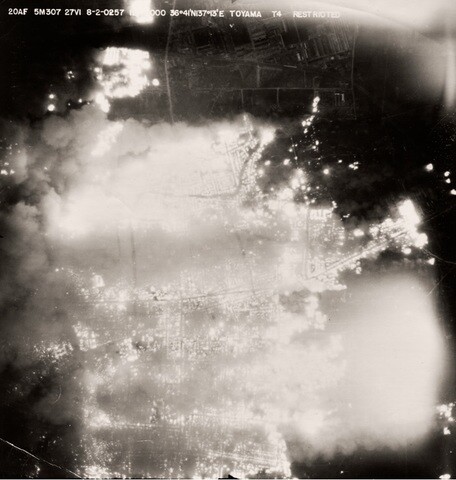

From October 1944 through July 1945, as Allied air strikes intensified over Tokyo and Yokohama, Dad lived in the crosshairs of Allied bombsights that widened their circle of terror night after night and then day after day, killing many friends and forcing him to dispose of their remains when assigned to body-burning work details.

Aerial bombardment photograph taken over Toyoma, October 2, 1945 by 20th Air Force. Image courtesy of Al R. Young.

Liberation finally came on August 29, 1945. In the chaos of release, Dad lost track of Jim. In fact, he tried to lose track of everything stained with the memory of his time as a POW. However, he crammed a duffle bag with belongings and memories he wanted to forget, and put Jim’s books on top of everything else.

On his way home, Dad kept leaving the duffle bag behind from ship to ship and port to port, trying to lose it. But from Tokyo Bay to Tulsa, it kept turning up, always a few days or weeks behind. Those were days for forgetting. The world had changed. Dad was out of step and anxious to make up for lost years. So the books followed him through his re-enlistment, marriage, a promising career in nuclear weapons, and the death of a daughter.

Life After War

The books were still there when I was born in Albuquerque in 1953. Owing to the loss of their daughter, my parents feared to even hope that they might bring me home from the hospital, but I survived. And after a year, they began to look ahead, wanting to offer me a better home environment than they knew how to create. Those were days before post-traumatic stress had a name, and Dad was still captive to the ghosts of Kawasaki, disabling headaches, paralyzing dreams, alcoholism, and other disabilities resulting from the beatings, psychological abuse, and starvation.

Faced with a crisis of parenting, Dad remembered the Book of Mormon and the talks he had had with Jim about the Church. So he looked up the Church in the phone book and left a message asking the missionaries to drop by. Time passed, the message was lost, and the missionaries never came; at least, not in response to the phone message.

Weeks later, two full-time missionaries, traveling through our neighborhood en route to their tracting area, decided to try just one more door before going home for dinner. They picked out our little house, which was in the middle of the block. No one answered the doorbell; Mother was in the backyard and Dad wasn’t home from work. But as the two missionaries mounted their bikes and were about to leave, Dad, who had worked a lot of overtime and had decided to come home early that afternoon, pulled into the driveway. Ignorant of Dad’s message asking that the missionaries drop by, they introduced themselves. Dad replied: “It’s about time. We’ve been waiting for you.”

The Books Return Home

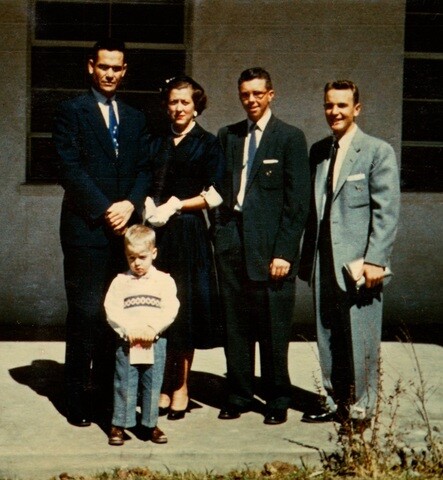

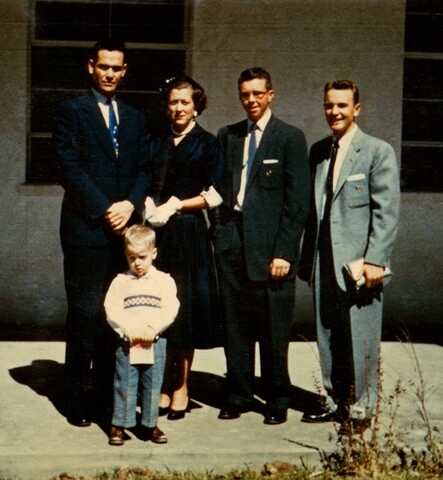

Mother and Dad were baptized in the spring of 1956 by Elder Glade Barney. In August of the following year, our little family was sealed in the Los Angeles California Temple. On the way back to Albuquerque, we stopped in Reno, Nevada. Dad had had no contact with Jim Nelson since the war but had heard he was living in Nevada.

The Alfred R. Young family, and the missionaries who taught them the gospel, at their baptismal service in Albuquerque, March 9, 1956. Image courtesy of Al R. Young.

We stopped at a pay phone and Dad found a listing for James Nelson. A phone call and a brief conversation with Mrs. Nelson confirmed that it was the same Jim Nelson who had been a prisoner of war in Japan, but he was still at work. We drove to the Nelson home and were sitting in the living room when Jim got there. The reunion was everything that could be wished, but nothing was said about the Church. Nothing, that is, until Dad reached down to pick up the two books he had hidden on the floor beside the couch.

“Jim,” he said as he lifted the volumes into view, “We’re on our way home from the Los Angeles California Temple where we’ve been sealed and thought we’d drop by to return your books.”

Jim was deeply moved by our visit in 1957 and always talked about his acquaintance with Dad as having been the mission he never served. Over the years, Dad made a special effort to keep in touch with Jim Nelson and Glade Barney—the two men who brought the gospel into his life.

Glade and his wife were part of our family’s celebration of Dad’s 90th birthday, and, in 2012, they attended Dad’s funeral. Jim Nelson’s daughter, Karen, also attended, her father having passed away in 1977. Until the day Dad died, he was true to what many people have heard him say: “If what I went through was the only way I could receive the Book of Mormon, I would do it all again—even knowing beforehand what I would have to endure—just to have that book.”

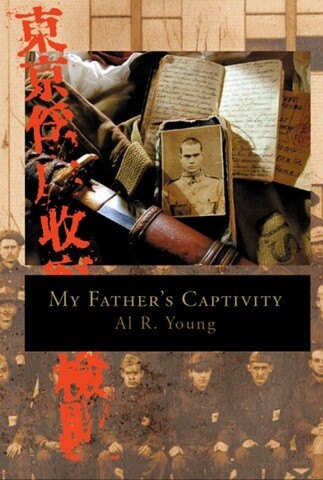

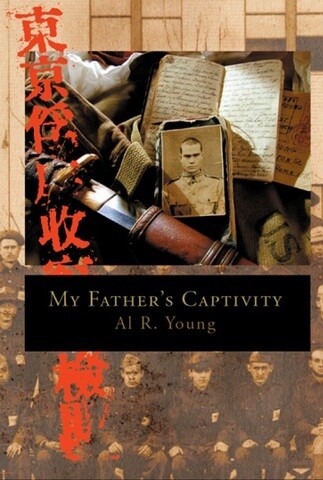

Al R. Young is an artist, writer, and founder of Al Young Studios. You can read more about his father's incredible story of how suffering the darkness of Japanese prisoner of war camps brought him to the light of the Gospel in My Father's Captivity.