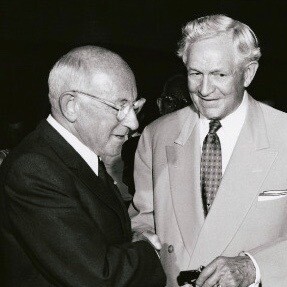

In some ways, the two men were polar opposites. DeMille was an icon in the 20th-century film industry who directed 70 motion pictures in a career that spanned four decades. Living in Los Angeles, he was referred to as “Mr. Hollywood.”1 President McKay, on the other hand, was dedicated to building Zion as prophet, seer, and revelator.

Although DeMille had formed good relationships with other religious leaders, which was simply good business,2 his friendship with President McKay reveals a deeper and long-lasting bond.

These two remarkable men were both directors—influencers who shaped the culture and character of their milieu. A decade after then-Elder McKay’s call to the holy apostleship, DeMille was working as the Lasky Company director-general3 when he lent his support to the production of an anti-Latter-day Saint propaganda silent film titled A Mormon Maid. Although DeMille was not responsible for the content of the film, he was responsible for the decision of whether or not it should be released in theaters. Having given his approval, it premiered on Valentine’s Day 1917, when anti-Church literature was rampant. The film was “arguably the most potent and important anti-Mormon film in the history of cinema” and “the most-advertised picture in the history of American cinema up to that time.” Critic reviews were extremely favorable of the film, and audiences came in droves to view it.4 Who could have guessed that nearly four decades later DeMille would be taking a private tour of the Los Angeles California Temple at the invitation of his dear friend, President McKay? What were the events that precipitated this ironic twist of fate?

►You'll also like: 5 Famous Actors Who Became Latter-day Saints

An Inside Look

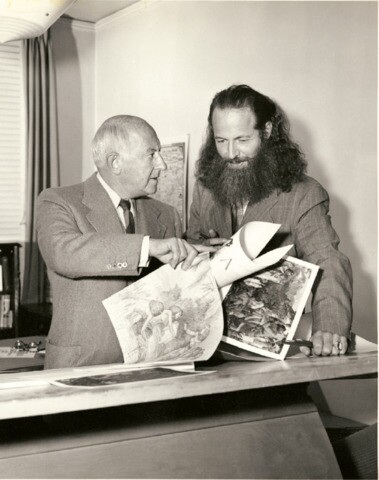

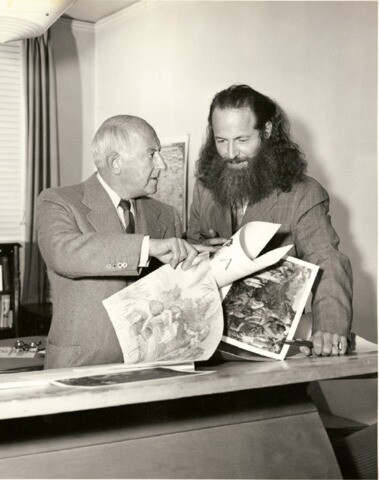

During the early 1950s, DeMille was immersed in the preproduction stages of his final and most successful film, The Ten Commandments. DeMille hired Latter-day Saint artist Arnold Friberg to design sets and costumes as well as promotional paintings for his epic film. Friberg became the catalyst in bringing Mr. Hollywood and the Latter-day Saint prophet together.5 In the course of their collaboration, Friberg and DeMille had many discussions that piqued DeMille’s interest in learning more about priesthood, temples, and all things pertaining to the religious film. DeMille asked Friberg to inquire into the possibility of meeting with President McKay because of his desire to tour the Los Angeles California Temple—then under construction—not far from DeMille’s workplace. The circumstances and series of events bringing these two unlikely friends together are described in McKay’s diary from July 11, 1954:

This morning Mr. Arnold Friberg . . . called at the office and explained . . . his position with Cecil B. deMille who has employed him to paint pictures and costumes . . . for the forthcoming motion picture masterpiece, “The Ten Commandments” which is being produced by Mr. deMille of the Paramount Studios. He said the next year they are going to Palestine to make scenes of the crossing of the Red Sea. They will also make scenes of Mt. Sinai. Brother Friberg also said that Mr. deMille confers with him from time to time about different phases of the Old Testament. For example, the conferring of the Priesthood upon Joshua. Mr. deMille said that this was the first instance of conferring of the Priesthood. Brother Friberg told him No; that Adam conferred the Priesthood upon his sons Seth, Noah, and others. Upon hearing this, Mr. deMille changed the scenes. . . . Furthermore, Mr. deMille is reading the Pearl of Great Price, the Book of Mormon, etc. During one of their conversations, on a certain subject, Mr. deMille said, “If I knew your President, I would telephone him upon this matter.” Brother Friberg told him that he was sure it would be perfectly all right to call me, but that Mr. de Mille was reticent about doing so. He said, however, that he would very much like to make my acquaintance. I told Brother Friberg that I would be in Los Angeles the first week of August, and at that time arrangements can be made for me to meet Mr. de Mille.6

The following month, August 5, 1954, DeMille and McKay met at Paramount Studios, making an instant connection. DeMille expressed his desire to go inside the temple.

“I’ll take you through myself,” President McKay said.7

A decade later in a BYU devotional speech, Friberg recalled:

That evening, I remember Mr. DeMille stopped me in the hall and was talking about President McKay. He says, “You know, I sure love that old buzzard.” . . . It was said with the greatest of affection. . . . He [DeMille] said, “When I talk to President McKay, I know I’m in the presence of a prophet. . . . It’s as if I were standing before the burning bush. I feel the same power.”8

Concerning this meeting in Los Angeles, McKay’s diary notes, “Mr. deMille received us graciously and had nothing but high praise for Brother Friberg’s work. . . . We were entertained most graciously and interestingly during our visit.” Following their time together, DeMille presented McKay with an inscribed copy of a Samson and Delilah handbook, containing research from his previous movie. The inscription read, “To President McKay, with respect—admiration, and now affection.”9

After meeting DeMille, President McKay composed a thoughtful handwritten letter to his new friend:

My dear Mr. de Mille, your graciousness to Mrs. McKay and me this afternoon, we shall ever cherish as one of the most interesting and informative experiences of our lives. Indeed we became so absorbed in your presentation of the magnitude and possibilities as well as the responsibility of your art that we failed to realize how grossly we encroached upon your valuable time. The more I think of it, the more keenly becomes my embarrassment. I not only apologize but beg your forgiveness. In the generosity of your heart kindly remember our overwhelming interest and forget our intrusion.10

Less than a week later, DeMille responded:

Thank you for your letter of August 5th. It was a great pleasure to see you and Mrs. McKay. I am the one who should ask forgiveness, if my absorption in my work—which is heavy right now—made you feel in the slightest degree uncomfortable. Far from being an encroachment, your visit for me [was] a privilege as well as a pleasure and one which I hope will be repeated if you should come to Los Angeles while I am filming THE TEN COMMANDMENTS here next year.11

Voice of God

The correspondence between these two men steadily continued. The following month, DeMille wrote, “When you were last in Los Angeles, you may remember our touching on the problem of portraying the Voice of God in my forthcoming motion picture of The Ten Commandments.”12

DeMille spoke of his efforts to produce such a divine voice and described that one of his staff members (“a brilliant electronic technician” named John H. Cope) had remembered “the unique quality of the Tabernacle organ and believes that the Vox Humana13 stop on this magnificent instrument will be the closest thing in the world to a musical representation of the Voice of God.”

►You'll also like: 18 Latter-day Saints on Reality TV Who Stood for Their Standards

DeMille asked President McKay for “permission to have Mr. Cope record the Tabernacle organ” and persuasively continued, “It would be a great contribution to a proper and reverent portrayal of the Voice of God and to the spiritual values which you, and we hope that The Ten Commandments will carry through the world.” Finally, DeMille thanked President McKay for the Gospel Ideals book President McKay had recently sent to him, which contained select public discourses compiled the previous year. The famed filmmaker said he continued to find this book “a source of new inspiration.”14

Not surprisingly, five days later President McKay and the First Presidency granted DeMille permission to use the tabernacle organ. The vox humana was then used to accentuate the deep base voice of former Tabernacle Choir member Jesse Delos Jewkes, who portrayed the singular voice of God for the film.

The following month, DeMille responded to President McKay’s note of permission:

Just returned from more than a week on Mount Sinai—one of the most unforgettably moving experiences of my whole lifetime—without further delay I must thank you and your counselors in the First Presidency for your permission to use the great Tabernacle Organ, as contained in your letter of September 23rd, and for the deep and, I am sure, prayerful interest which you and your counselors are taking in the production of The Ten Commandments. I hope we and our work may be worthy of it.15

Touring the Temple

The following year, President McKay and his wife, Emma Rae, visited DeMille’s studio in Los Angeles on July 21, 1955, during active filming. On this date, McKay’s diary notes the following entry:

We spent three hours on the set and were intensely interested and amazed at the magnitude of the whole project - - what a stupendous thing it is to produce such a play as the Ten Commandments.! I am impressed more than ever with Cecil B. deMille’s ability - - he is a great director!16

Less than six months later, President McKay took DeMille and his small staff of six through the Los Angeles California Temple. This special private tour took place January 16, 1956, two months before the temple was dedicated in March.17

The local news picked up on DeMille and his Paramount Studios entourage touring the temple. Soon, “DeMille Visits L. A. Temple” headlined the papers. The papers also captured the mutual admiration that DeMille and McKay had for each other. DeMille informed the press that the private tour “was a great privilege and a pleasure.” As President McKay bid farewell to the group, he said of DeMille, “Here is one of the true noblemen of this world.” DeMille described President McKay to a reporter as “one of the great souls that I have been privileged to meet in this world; he has understanding; he has the true spirit of Christ; he is a great pioneer of God.”18

Apparently, the temple tour had a spiritual impact on DeMille. The Deseret News reported that President McKay described the filmmaker as “a longtime friend and interested student and admirer of the Church and its people” and noted he “seemed deeply impressed by his visit to the new temple as were the other members of his party.”19 Friberg later recalled that President McKay’s only explanation to DeMille regarding the temple’s purpose was “to take man from physical man to spiritual man.”20

In his autobiography, DeMille described President McKay as “a great-hearted, lovable man who is literally a latter-day saint” and a man “through whom the Divine Mind shines crystal clear.” In addition, the Episcopalian DeMille noted, “Others like me might be more regular church-goers if there were more McKays.”21

On Thursday, August 2, 1956, DeMille arrived in Salt Lake City to provide a preview of his epic film, The Ten Commandments.22 DeMille biographer Scott Eyman noted that this was the film’s “sole public preview,” despite DeMille’s staff warning him that Salt Lake City would not represent a national audience.23

Yet DeMille reasoned, “If the deeply religious, serious-minded Latter-day Saints of Salt Lake City approved . . . so would millions of others, of other faiths, through the world.”

►You'll also like: A Latter-day Saint in "Stranger Things" Season 3 + 10 Other Funny Latter-day Saint Mentions in TV

DeMille also confessed, “I may have had a personal, almost selfish, reason for wanting to preview in Salt Lake City: it gave me another chance to spend some time with . . . the President of the Mormon Church, David O. McKay. There are men whose very presence warms the heart. President McKay is one of them.”24

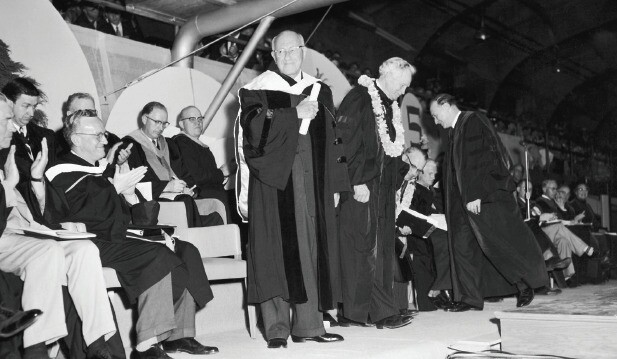

Soon thereafter, DeMille received an honorary doctoral degree from Brigham Young University and spoke at the spring commencement exercises on May 31, 1957, following an introduction by President McKay. On that occasion, President McKay said his dear friend was “one of those living light-fountains in whose presence one feels inspired and uplifted.” President McKay felt his famed friend’s greatness was “not only in his ability to choose the right . . . but because of his soul, his faith in God, his confidence in his fellow men,” adding, “I love him because of his nobility.”25

DeMille then spent the bulk of his well-prepared speech26 on the importance of law and keeping the Ten Commandments, readily apparent in his landmark film nominated for seven Academy Awards. He also spoke of his friend President McKay: “One of the most valued friendships that I have [is] the friendship of a man who combines wisdom and warmth of heart. . . . I have known many members of your Church . . . but David O. McKay embodies more than anyone that I have known, the virtues and the drawing-power of your Church.” DeMille then said, “David McKay, almost thou persuadeth me to be a Mormon!”27

A Parting of Friends

As the year drew to a close, David and his wife, Emma Rae, sent a Western Union telegram to DeMille stating:

YOUR WIRE DELIVERED XMAS DAY IN THE MIDST OF FAMILY FESTIVITIES. . . . MAY THE NEW YEAR BRING YOU RESTORED HEALTH HAPPINESS AND CONTINUED SUCCESS IN YOUR BENEFICIAL SERVICES FOR THE BETTERMENT OF MAKING [MANKIND].28

The well wishes for a restoration of health were sent due to a recent heart attack DeMille had suffered in Egypt. On June 18, 1958, he suffered another heart attack, which was more serious than the previous one.29 DeMille later passed away at his home on January 21, 1959, at age 78.

On the day of DeMille’s death, President McKay sent a telegram to the DeMille family stating that DeMille “merits the welcome, ‘well done that good and faithful servant; enter thou into the rest prepared for the just.’ Heartfelt condolence to his bereaved Loved Ones.”30 A Deseret News reporter called at President McKay’s office that same day to request a statement on his friend’s passing. President McKay stated:

I am deeply grieved. He was a great man, fearless in the defense of what he considered to be right. I consider him the greatest leader in the motion picture business, really a world benefactor. He was a man of high ideals. . . . I was proud to be counted among his friends.31

A few days after the passing of DeMille, President McKay received a letter from the Paramount Pictures Corporation notifying him of a gift that would soon be coming, “an especially bound copy of the screen play for The Ten Commandments.” In addition, President McKay learned that there were just 25 of these works printed and that only 19 of them were inscribed—one of which was President McKay’s.32

Both David O. McKay and Cecil B. DeMille had a great impact on their generation. President McKay wore out his life building what he believed to be God’s kingdom on earth. While DeMille spent most of his life in the flash of Hollywood, he never seemed influenced by it.

►You'll also like: 5 Times TV Shows Were Mentioned in General Conference

Because of the laws both DeMille and McKay lived, they were both considered men of honor, decency, and nobility in their different spheres of society. The genuine friendship of David O. McKay and Cecil B. DeMille was not only unexpected but remarkable, shining a bright light down the corridor of history and yielding a more favorable view of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the midst of the 20th century.

Lead image courtesy of L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Brigham Young University.

This article is adapted from one published in BYU Studies Quarterly, volume 57 number 4.

Notes

1. Sumiko Higashi, “An American Spectacular: The Life and Career of Cecil B. DeMille,” in The Register of the Cecil B. DeMille Archives, MSS 1400, compiled and edited by James V. D’Arc (Provo: Utah, Brigham Young University, 1991), 1.

2. DeMille’s papers reveal correspondence with various religious leaders.

3. Higashi, “An American Spectacular,” 3, notes, “DeMille’s life changed dramatically toward the end of 1913. According to a story that has since become legendary in motion picture history, DeMille joined a venture with Jesse L. Lasky, a vaudeville producer with whom he had collaborated on musical shows; Samuel Goldfish (later Goldwyn), Lasky’s brother-in-law and a glove salesman; and Arthur Friend, an attorney. Pooling resources, they founded the Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Company (named after Lasky because he was best known) to produce feature film adaptions of stage and literary works for middle-class audiences.”

4. “A Mormon Maid,” Mormon Literature and Creative Arts, Brigham Young University, https://mormonarts.lib.byu.edu/works/a-mormon-maid/.

5. For more information on Friberg, see Velan Max Andersen, “Arnold Friberg, Artist: His Life, His Philosophy and His Works” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University Department of Art, 1970).

6. The David O. McKay diaries are located in MS 668, David O. McKay Papers, Manuscripts Division, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City. This reference taken from box 33, folder 4, of the McKay Diaries (hereafter cited as DOMD), July 11, 1954, underlining original.

7. Arnold Friberg Interviews by Gregory Prince, August 4, 2000, November 16, 2000, cited in Prince and Wright, David O. McKay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism, 259.

8. Arnold Friberg BYU Devotional (April 29, 1964).

9. DOMD, August 5, 1954

10. Letter of President David O. McKay to Cecil B. DeMille, August 5, 1954, Cecil

B. DeMille Papers, MSS 1400, box 482, fd. 13, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, hereafter cited as LTPSC. Cecil B. DeMille Papers hereafter cited as CBDP.

11. Letter of Cecil B. DeMille to David O. McKay, September 18, 1954, CBDP, MSS 1400, box 482, fd 13, LTPSC.

12. Letter of Cecil B. DeMille to President David O. McKay, September 18, 1954, CBDP, MSS 1400, box 482, fd. 13, LTPSC.

13. Vox humana is the Latin word for “human voice” and is contained in a box that is continually shut. Organ swell pedals determine the tone of what can be admitted from the box at various levels. See The Encyclopedia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences and General Literature With New American Supplement, 30 vols., ed. Day Otis Kellogg, (New York: The Werner Company, Company, 1898), 17: 836.

14. Letter of Cecil B. DeMille to President David O. McKay, September 18, 1954, CBDP, MSS 1400, box 482, fd. 13, LTPSC.

15. Cecil B. DeMille to David O. McKay, October 25, 1954, box 482, folder 13, CBDP

16. DOMD, July 21, 1955.

17. DOMD, January 15–19, 1956, Ms 668, box, 36, fd. 4, newspaper clipping, “DeMille Visits L.A. Temple,” The [Los Angeles] California Intermountain News, January 26, 1956.

18. “DeMille Visits L.A. Temple,” The [Los Angeles] California Intermountain News, January 26, 1956, newspaper clipping in DOMD, January 15–19, 1956.

19. “DeMille Is Guest: Pres. McKay Back from Temple Visit,” Deseret News, Church Section, January 21, 1956, newspaper clipping, DOMD, January 15–19, 1956.

20. Friberg, interviews, August 4, November 16, 2000, cited in Prince and Wright, David O. McKay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism, 259.

21. Hayne, Autobiography of Cecil B. DeMille, 433–34.

22. The 1956 film was a partial remake of an earlier silent film by the same name launched in 1923.

23. Eyman, Empire of Dreams, 474.

24. Hayne, Autobiography of Cecil B. DeMille, 433.

25. Introduction by President David O. McKay, in Addresses of the Eighty-Second Annual Commencement Exercises and Baccalaureate Services, 1957, in Brigham Young University Bulletin 54, no. 17 (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University, 1957), 1, Perry Special Collections.

26. It is readily apparent that DeMille had a gift for speaking, as evidenced by his commencement address, which was carefully organized and executed. Evidence of such preparation is revealed in notes DeMille made over a year before the commencement address: “There are three approaches. this is a graduating class. One is their duty to their God first, duty to their country second and their home third. I would talk on those three things and in the commandments you have those three things. Definitely provided for.” “Notes for Possible Mormon talk,” April 17, 1956, box 482, folder 13, CBDP.

27. Cecil B. DeMille, in Addresses of the Eighty-Second Annual Commencement, 3.

28. David O. McKay to Cecil B. DeMille, telegram, December 29, 1957, box 482, folder 13, CBDP.

29. Hayne, Autobiography of Cecil B. DeMille, 438.

30. DOMD, January 21, 1959.

31. “DeMille Dies of Heart Ill,” Deseret News, January 21, 1959, copy of newspaper clipping in DOMD, January 21, 1959.

32. Paramount staff member Ann del Valle to David O. McKay, January 26, 1959, copy in DOMD, February 6, 1959.