*The following article previously ran on LDS Living in October 2015.

"It’s conference time again.” During 1971, these four words were part of the brief daily communication between rooms two and three at Camp Unity, a Vietnamese prisoner of war camp. They stirred emotions, brought back memories, boosted morale, and gave a needed reminder that there was still good in the world. They meant that the places I dreamed about still existed. Hearing those words was a very significant, memorable event.

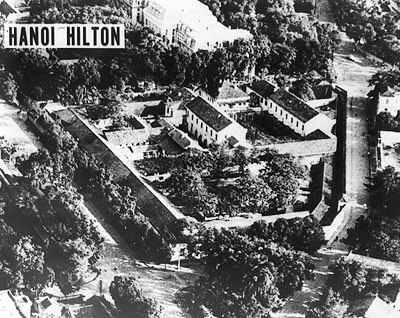

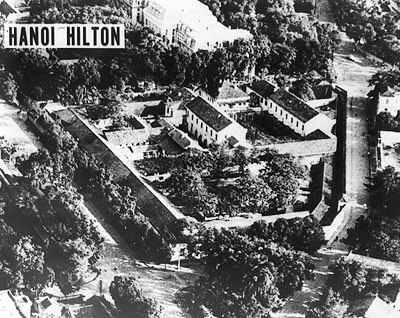

On August 24, 1967, the F-105 I was flying over North Vietnam was hit by ground fire while pulling off a target on the railroad northeast of Hanoi, near the Chinese border. It caught on fire and pitched down uncontrollably. I ejected, and in the chaos that followed, I was captured and became a prisoner of war in Hanoi. During that time I stayed in camps we called the Hanoi Hilton, Annex, Zoo, Faith, and Unity. Days seemed to be a week long and nights were longer. Four years of isolation often made me question what was real, imagined, or a dream.

I was allowed to write my first letter on Dec 13, 1969—more than two years after I was shot down. In it I wrote: “These are important: temple marriage, mission, college. Press on. . . . Set goals, write history, take picture twice a year.” After my family and friends back home in Utah received this letter, my military status changed from missing in action (MIA) to prisoner of war (POW). After a rescue attempt at nearby Son Tay on November 21, 1970, they moved everyone to big rooms in the Hanoi Hilton. There were 40 to 50 of us crammed in each of seven cells.

Though communication between rooms was difficult and rarely personal, one long-time prisoner, Air Force Captain Smitty Harris, taught a tap code to others. By chance, he had learned it at survival school. It wasn’t part of the curriculum, but an instructor had told him about British POWs during WWI or WWII communicating between buildings by tapping on pipes that ran between them.

They put the letters of the alphabet in a five by five box, leaving out the letter ‘K.’ Each letter was identified by two taps; the first designated the column, the second the row. For example, the letter ‘A’ was tap, pause, tap while the letter ‘Z’ was five fast taps, pause, five fast taps.

This communication system worked well for us most of the time, but some rooms were corner rooms separated by a hall or stairwell. The distance made it impossible to communicate by the usual method of tapping on the wall. Instead, because the windows were covered with straw or bamboo mats, messages were flashed one letter at a time through holes in the mats, using the tap code.

There was usually a period during the early afternoon when the guard activity slackened. That is when we tried to communicate.

Our captors attempted to exploit us for antiwar propaganda and realized we were much more vulnerable if they could keep us isolated. They did everything they could think of, including torture, to stop communication.

Four of us were in a room in Camp Unity for a year before we were able to communicate with other POWs. It was in this way that I learned about and began communicating with fellow members of the Church in room three: Jay Jensen and Larry Chesley. And though we were happy to finally be able to communicate, we had more questions than answers.

Who is in the camp? Who is the senior ranking officer? What are his guidelines for escape? What torture or threats have others received? Any ill or injured? Any news from new guys, recently shot down? Anyone get to write or receive mail? Any news from the real world?

Along with the questions, there were words of humor, comfort, and support sent for someone ill or to those being interrogated more than the rest of us. Some with better memories passed along quotes from the Bible, poems, Shakespeare, and their own creations. We were probably the last group on earth to learn that man had been to the moon. We only found out after someone received a package from home with a sweetener packet that had a picture of Neil Armstrong on the moon.

One day, in 1971, Larry received a letter from his mother in Burley, Idaho. When the official business part of our inter-room communication was slack, Larry was able to tag this personal message from the letter on at the end. “For Hess. Chesley received letter from mother. She wrote, ‘It’s conference time again. President Smith conducting.’”

My heart was softened and the memories flowed at those words. Memories of conferences past—of spring tulips and fall colors, of the Tabernacle, and the inscriptions on the wall behind the flag pole and Salt Lake Temple. I tried to recall what was on the wall about liberty, governments, and The Way.

I recalled attending conference with my deacons quorum. I remembered being in uniform and receiving priority treatment by being allowed to watch it in the Tabernacle. I could hear in my mind the words, "Once more we welcome you to Music & the Spoken Word from the Crossroads of the West" and the choir singing, "Gently raise the sacred strain, for the Sabbath's come again, that man may rest." It seemed strange that I thought of Elder LeGrand Richards talking so rapidly and enthusiastically about “A Marvelous Work and a Wonder” and “Voices from the Dust.”

Yes, those four words, “it’s conference time again,” were not only unexpected, they were uplifting and comforting. But the message was also perplexing. David O. McKay had been President of the Church when we were shot down. What did ‘President Smith is conducting’ imply? Was President McKay ill? Later we learned that President McKay had passed away, and that, during the final years of our imprisonment, President Joseph Fielding Smith had served as the 10th president of the Church, from 1970 to 1972.

Shortly after our release in February and March of 1973, I found myself listening to another prophet, President Harold B. Lee, as he presided at the 143rd Annual General Conference in the Tabernacle. In his introductory remarks, he recognized the presence of recently released POWs Captain Larry J. Chesley, Major Jay C. Hess, and Lieutenant Commander David (Jack) Rollins, reminding me again of that hopeful message from Sister Chesley the year before.

Thank you, Sister Chesley, for including that most significant message in your letter to your son. Thank you Larry ‘Lucky’ Chesley for caring enough to pass those hallowed words on. “It’s conference time again”—four words that still stir emotions and have a world of meaning.

Lead image from ChurchofJesusChrist.org, all others from Wikimedia Commons